An Observer of World Crises

GA 36

Translated by Henry B. Monges

In his book The Three Crises; an Inquiry into the Present Political World Situation, J. J. Ruedorffer offers an exposition of world events which could only be the work of a man whose experience has enabled him to develop an opinion in conformity with facts. From the author's description, it is on every page apparent that he has for long years lived deeply with his ideas in the events taking place around him. He remarks in his Introduction: “This Inquiry was written in May 1920 as a supplement to an enlarged, new edition of my Basic Trends in World Politics. But in accordance with the wishes of my publisher it is now issued as a separate book.”

We may read this book as the confession of a man who asks world history what it has to say concerning the present state of the world. Without any political party prejudices, he seeks a reply to this question. But his opening words express only despair: “Without comprehension my contemporaries stand confronting world events. What is happening, from what causes, and to what end? This best of all worlds was, to be sure, intelligent up to the present, and has now fallen into a state of insanity. Revolution follows revolution, and peoples rage against themselves. No! the world was neither intelligent until recently, nor has it now suddenly fallen prey to insanity. Civilization has been cleft from the beginning by a gaping abyss. There are periods of history which conceal it under all sorts of underbrush. There are human generations which either walk along its edges carefree or try to deny its existence by closing their eyes; and there are other generations which, when compelled to gaze into its depths, wish to turn away, shuddering, yet are unable to do so. From an age of the first kind we have entered an age of the second.”

Three present-day crises are described by the author. Evidence of the first he sees in the position into which nations—especially the European—have been forced, and in which they find it impossible to arrange their mutual relationships without clashes. A second crisis is evident to him in the fact that the governments of the various states have gradually lost their power to the contending political parties, so that what happens does not depend upon the governments, but upon the mechanism in the play of party-influence. A third crisis is apparent in the sum total of the social strivings which press up to the surface from the subconscious depths of the masses, who have no insight into the results of their own efforts, indeed, who, in their very desire to bring about an improvement in the present conditions of life, themselves destroy the possibility of a general social community of human beings.

At the conclusion of each one of the three chapters dealing with these three crises stands a confession of despair, summarizing the content of the author's research. The first chapter concludes thus: “The untenable condition of Europe before the war has now become, through war and peace, a hundredfold more untenable. At that time a grand but thoughtless state of prosperity—in danger of being wrecked one fine day because of the instability of the European balance of power—was threatened with being swallowed by a world war. It was to the common interest of the European peoples to avoid this world war. Lack of insight into their common interest, lack of cool political leadership—independent of demagogues, and able to survey the common danger—finally permitted it to break out. The war is now over; it has ruined every single nation on the European continent and to the last degree disorganized the whole. The peoples of Europe, unable under present conditions even to live, to say nothing of healing the wounds of war, are individually and collectively confronted with a choice either of finding and following with determination new ways, or of perishing completely.”

Of the second crisis he says the following: “This sickness of the political organism deprives the reasonable of leadership and permits the handing over of political decisions to manifold.

irrelevant, subordinate, and private interests. It limits the freedom of movement, disperses the political will, and, besides this, is followed in most cases by a dangerous governmental instability. The period of unruly nationalism before the war, the, war itself, the condition of Europe after the war, have all placed enormous demands on the reasoning ability of the states, on their calmness, and on their freedom of movement. The fact that, with the increase of their tasks, the nations' ability to master them did not also increase but decreased, has completed the catastrophe. If democracy is to endure, it must be honest and courageous enough to state the facts, although by so doing it appears to testify against itself; Europe stands face to face with ruin!”

In the third chapter we find the following: “It is a profound tragedy how every attempt at a better handling of affairs, every word of reform, is caught in the meshes of this catastrophe and over and over ensnared, so that it finally falls to the ground without effect; how the European bourgeoisie, either thoughtlessly clinging to a false notion of the age—continued progress of mankind—or just plodding along the customary road, lamenting their lot, do not see and do not want to see that they are nourished by the stored up energy of previous years, and scarcely capable of recognizing the infirmities of the present world-order, to say nothing of bringing forth out of themselves a new one; how, on the other hand, the proletariat, becoming in nearly all countries ever more radical, convinced of the un- tenability of the present state of affairs, and believing themselves the bringers of salvation by sponsoring a new world order, are in reality, only the unconscious instruments of destruction and ruin, including even their own. The new parasites of economic disorganization, the complaining opulent of yesterday, the petit-bourgeois sinking to the level of the proletarian, the credulous worker laboring under the delusion that he can establish a new world-order, all seem embraced by the same catastrophe, all seem to be blind men digging their own graves.”

We would not turn aside from this confession so distressed, did the writer's style and attitude betray the literary observer, rather than the practical man who wants to write factually because he feels himself standing in the midst of events. After one has read the three chapters speaking of the downfall of civilization, the anxious soul asks: how does the author of such an exposition think about the question: What ought to happen?

In answer we read: “Only a change of the world's mind, a change of will in the participating Great Powers, can create a Supreme European Council based on reason.”

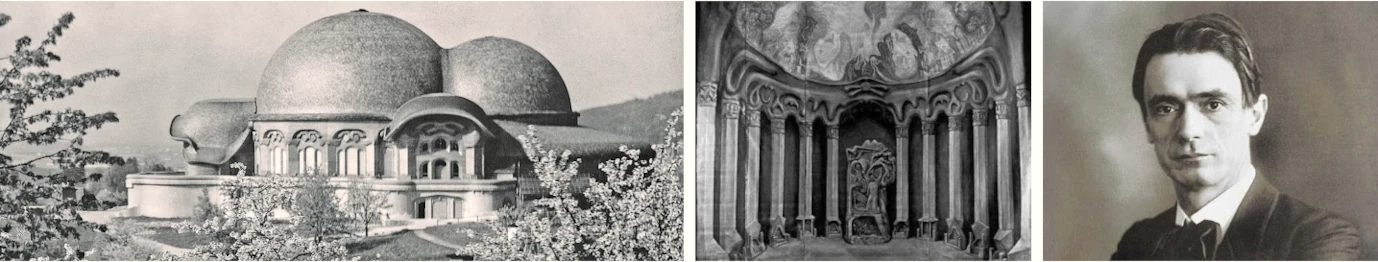

There is no indication how this “change of mind,” this “change of will,” is to be accomplished. Even after such a stirring insight into the impossibility of continuing with the old ideas, there is no evidence of the courage required to seek the conditions upon which recovery depends. If we seek these conditions, we come to what has often been expressed in this magazine [The Goetheanum]: The social organization of mankind has at all times received its nourishment from the spiritual content of the human evolutionary stream. Ideas which should sustain the social organization, as well as the economic life, must stem from the union of men's souls with an actual spirit-world. Otherwise these thoughts are merely intellectual. But the sense for such a union with the spirit-world is lacking in just such a personality as the author of the Three Crises. He is able to think about what his senses perceive, and about what his intellect can combine from those perceptions. Beyond this—only a blank. For after this negative confession another confession should come forth; namely: old ideas were created out of living spirit, and have, indeed, fulfilled their mission; we cannot continue to be nourished by the “stored up” ideas of earlier periods. New ideas must be born; to accomplish which, a union with the spirit-world is a necessity. But to such a continuance of the confession belongs the courage not only to speak of “change of mind” and “change of will,” but to acknowledge that mankind's turning away from a vivid experience of the spirit has led to the impossibility of recognizing in full consciousness the reasons for the catastrophe that threatens, although these are seen. Mr. Ruedorffer sees clearly enough; but he does not understand what he sees. Only the sustaining power of ideas born of the spirit, ideas which permit warmth to flow into human souls, which permit the human being to look upward from earth-bound daily labor to his world mission, to his relationship with the universe, only the sustaining power of such ideas will guide his hand to fruitful work and enable him to establish a human brotherhood. Today the world disdains those who speak thus of the spirit. Civilization, however, will recover its health only at the cessation of this disdain.

We may speak of a “three-membering” of the physical human organism: the nerve-sense organism, the rhythmic organism, and the metabolic-limb organism. We must acknowledge that the two other organisms decay when the metabolic organism no longer brings real substances to the whole. In the social organism a reversed condition prevails. This organism is composed of the economic, the politico-rights, and the spiritual organisms. The other two decay when the spiritual organism does not receive real ideas, born of spiritual experience, and impart them to the other two. Just as the human body needs real substance to sustain it, so does the human social organism need real spirit.

There are still people of the present day who confess something like fear of the spirit. These people are inclined to scent superstition, sentimental enthusiasm, lack of scientific method, when someone speaks of the spiritual world, not just in superficial phrases, but in a manner that indicates its real content—an accepted procedure when speaking of nature and history. Only when this secret fear is overcome can we know what really is contained in present world events. If the conquest is not achieved, we stop short at mere seeing. The book in review speaks only of this sort of seeing.